1. MH: Greetings Stephen. Congratulations on the release of the third book in your AEF series. Please tell our readers why you decided to commit a major part of your life and so much creative energy to a project on the First World War.

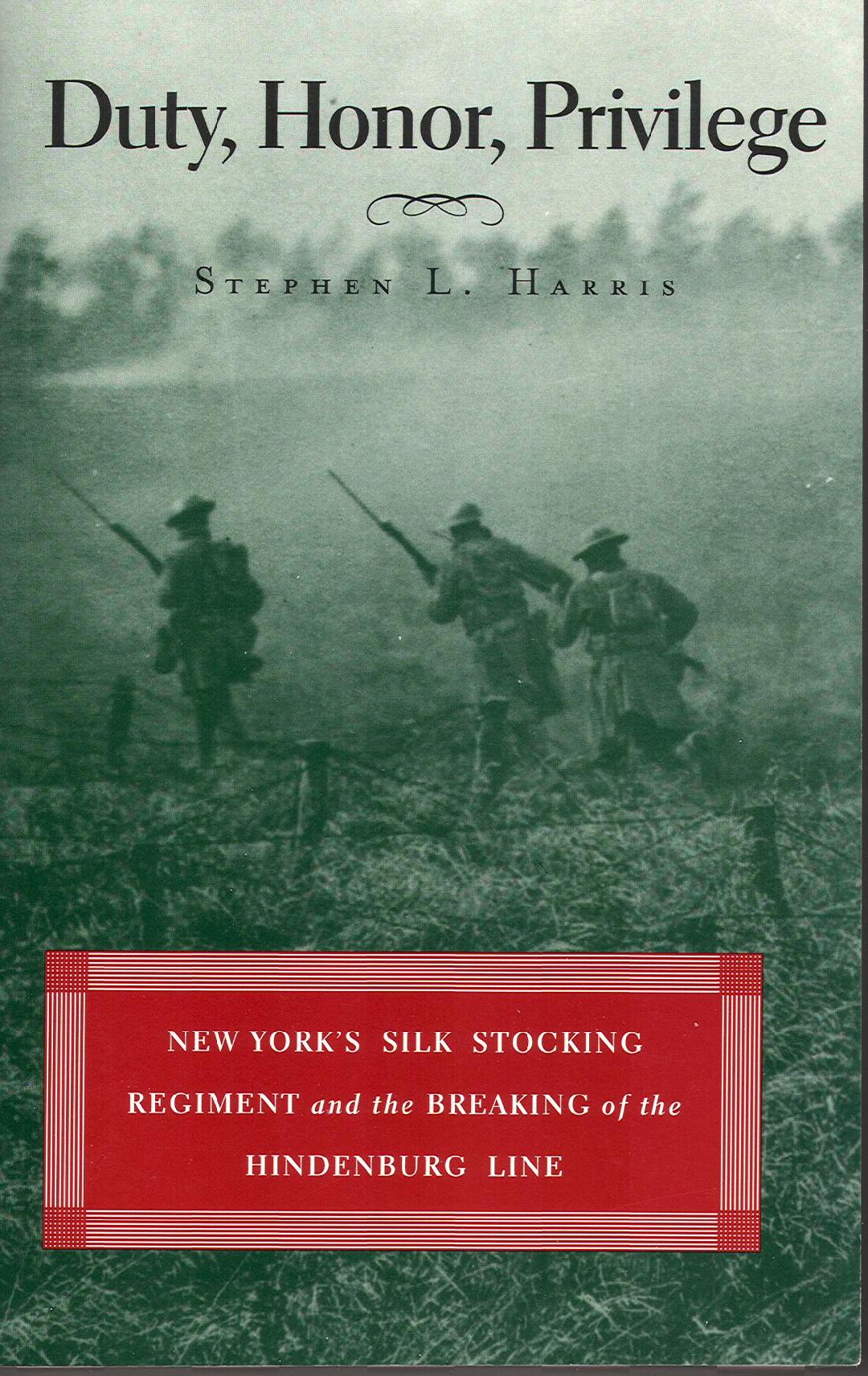

SH Response: When I started working on my first book, “Duty, Honor, Privilege,” the thought of writing a war trilogy hadn’t crossed my mind. I wanted my second book to be a history of the Olympic decathlon. At that time I was editor of the Journal of Olympic History and had just finished “100 Golden Olympians,” a book for the United States Olympic Committee that honored America’s greatest living champions. So I hadn’t yet committed myself to being a writer of war stories. Now, ten years later, I’m hooked on the Great War. And I don’t see an end in sight.

2. MH: How did your project evolve into a trilogy of histories of regiments from New York?

SH Response: In the middle of writing “Duty, Honor, Privilege” I started to describe an incident at Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina, where New York’s 27th Division was training. The 15th New York, the African-American regiment from Harlem, had just been kicked out of camp, in fact kicked right to France. As the 15th departed Wadsworth, the old 7th Regiment, the 107th, formed a double line, like a gauntlet, and as the blacks marched through, the white boys, many of them from Manhattan’s silk stocking district, sang to them George M. Cohan’s stirring “Over There.” At that moment I knew I had to tell the story of Harlem’s Hell Fighters. A similar incident in my second book then led me to the Fighting 69th and Father Duffy. This time, the 15th, now at Camp Mills and preparing to sail for France, feared an attack by an Alabama regiment that wanted to bloody every black it saw. When word reached the 15th that an attack was imminent, soldiers from the 69th slipped their New York comrades-in-arms, ammunition for their rifles. A light flicked on in my brain. All three New York City’s National Guard regiments in the Great War were connected in many ways. Write a trilogy about them.

3. MH: Did any of your family serve in the three regiments or other AEF units?

SH Response: I had two great uncles in the war. Raeburn Van Buren, my grandmother’s brother, served with the 7th Regiment. He was a young magazine illustrator who became art editor of the 27th Division’s magazine, The Gas Attack. At war’s end, the New York Times called him the American Bairnsfather, after the famous British illustrator Bruce Bairnsfather. I knew him well and after he died I read all his letters that he’d sent to his mother, my great grandmother. He was my inspiration for the book on the 7th Regiment. My other uncle, Alfonso Gibbs Hofmann, served in the 137th Ambulance Company of the 110th Sanitary Train. He was a newspaper reporter for the Kansas City Star and a pretty good poet. I have a number of his letters, too. I also have a rather romantic poem he wrote about his French nurse while convalescing in a hospital. He entitled it “When She Goes By.”

4. MH: Why did you choose all National Guard formations for your trilogy, rather than including, say, a regiment of draftees?

SH Response: I picked the 7th Regiment because of my great uncle, Raeburn Van Buren. Our long conversations and then the content of his letters from the front convinced me that the 7th would make a heck of a story. The fact that it was a National Guard outfit was coincidental. After I finished “Duffy’s War,” I contemplated a book on the 77th Division, which includes the Lost Battalion. But the book’s already been done and the Lost Battalion’s been overdone-although a great opening scene would have Maj. Charles Whittlesey after the war, standing on the deck of a ship at sea and, just before he jumps into the dark, cold waters to his death, flashes back to the horrors of war that obviously leads him to commit suicide.

5. MH: I find it interesting that the three New York regiments served under different commands: British, French and AEF. How did the experiences differ for the men? Did those under foreign command feel they missed something?

SH Response: They missed a lot, I think. For the 7th Regiment, attached first to the British Fourth Army and then to the Australians, its men never fully got credit for what they accomplished. Out of sight out of mind, as far as General Pershing, I believe, was concerned. The men of the 15th, or 369th Infantry, felt like orphans when it came to the AEF. Nobody wanted them. As their commander said, “We were left on the doorstep of the French army.” But there they found a home. By the way, the 69th also served with the French during the opening of the Champagne offensive, but was then folded back into the AEF for the rest of the war.

6. MH: The Silk Stocking Regiment [107th Inf, 27th Div.] was actually only half composed of the upper crust of New York City. They were combined with a unit from the agricultural upstate area known as “Appleknockers”. How did this mixture work out?

SH Response: The mixture worked out surprisingly well, even if the 7th gained the upper hand because most of its officers took control of the regiment. After the 1st and 7th were combined and had lost their historical numerical designations, Col. Willard Fisk, called all the troops together and told them that they had not in fact lost their historical designations. They were “still the 1st and the 7th with nothing in between. The 1-0-7th!” In one incident, a professional boxer from upstate picked a fight with a pint-sized corporal named Merritt Cutler. Cutler knew that even though he’d lose he had to fight the boxer. He was soundly thrashed. The boxer picked him up and carried him inside a tent. He then stepped back outside and barked to his fellow appleknockers that because Cutler had stood up against him he’d follow that corporal to the gates of hell and everyone better do the same.

7. MH: In our preliminary discussions, you mentioned that members of the 107th received more Medals of Honor in one day [Four on 29 September 1918] than for any regiment in the Great War. How did this remarkable feat come about?

SH Response: On the 29th, the 107th attacked probably the strongest point of the Hindenburg Line without a rolling artillery barrage. The ground they marched over was covered with barbed wire and hidden tunnels, and as soon as they passed by one of those tunnels Germans streamed out and gunned them down from behind. The fighting was fierce and the 107th lost more men killed in one day of battle than any regiment in United States history. Three machine gunners, Sgt. John Latham and Cpls. Alan Eggers and Thomas O’Shea, saved a tank crew and then for most of the day held off the Germans, and for that they each received the Medal of Honor. Pfc. Michael Valente singled- handedly attacked an enemy trench seething with machine gunners, running along the edge, tossing in hand bombs. It took the government ten years to recognize his valor with the Medal of Honor.

8. MH: How many veterans of the three regiments did you get to meet personally? Do you have any personal memories of them you would like to share?

SH Response: Unfortunately only one. That, of course, was my great uncle. He lived to be 98. He had a small studio in his garage in Great Neck with some of his artwork on the wall (he drew the comic strip “Abbie an’ Slats”) along with his bayonet and helmet with the 27th’s insignia on it. I’d spend hours with him, talking about his days when he first came to New York seeking fame and fortune, his soldiering experience and his life as an illustrator and comic-strip artist.

9. MH: Who were your favorite personalities from each unit? Let’s leave out Father Duffy, we will discuss him next.

SH Response: Obviously, in the 107th it would be my great uncle. But also Cpl. Billy Leonard from Flushing, a newspaper editor who thrilled at everything he experienced-from boot camp to the front- line trenches. Everybody adored him. He was the first soldier in the 27th Division to be killed in action. In the 369th, the one and only Lt. James Reese Europe. An early giant of jazz, Europe, although a machine-gun officer, organized perhaps the greatest regimental band ever and took it on a tour of France while later distinguishing himself as the first African-American officer in the war to enter no-man’s land. I believe his life’s story would make a terrific movie. In the 69th, Capt. Van Santvoord Merle-Smith, certainly one of the wealthiest men in the regiment who before the war had helped organize the Plattsburg officers training camp. I believe Merle-Smith should have earned the Medal of Honor for his valiant action when his L Company was nearly annihilated during the battle of the Ourcq River.

10. MH: Father Duffy has this interesting Times Square and Military association. What are some of the keys to understanding this unique man?

SH Response: His love for all humankind. It shines so brightly in his deeds, both in his humble parish in the Bronx and later in Hell’s Kitchen and, of course, on the blood-stained soil of France. I think Father Duffy put it best when he said, “I cannot claim any special attribute except that of being fond of people. Just people.”

11. MH: I assume the veterans of the three units had reunions and ceremonies to honor their fallen comrades for decades after the war. What can you tell us about these practices? Did they have “Last Man” clubs.

SH Response: There were a number of last man’s clubs strewn throughout New York state, each with that sacred bottle of liquor that would be finished off by the last man standing. But one of the lasting legacies of the New Yorkers was the role some of them played in the founding of the American Legion, most notably Capt. Hamilton Fish Jr. of the 369th Infantry. In fact, if you went around to every American Legion post in the state I’d bet you’d find that many of them are named for fallen soldiers who had served with the old 7th, with Harlem’s Hell Fighters, and with the Fighting 69th.

12. MH: Other than the normal channels of research, such as the National Archives, the Military History Institute, etc., do you do anything special?

SH Response: Once I obtain the roster of the regiment my wife and I go through almost every name and look for obituaries in the Times and other New York newspapers. It’s time consuming. But always rewarding. By that I mean we are able to track down surviving family members, sons or daughters or grandchildren. From them we often obtain never-before-seen diaries and letters. In one instance, I tracked down the son of Capt. Basil Elmer of the 69th. When I talked to him he wondered how he could possibly help. I asked if he had any letters. He said, “You hit the jackpot.” His father wrote one or two letters every day. They were all bound in five huge notebooks. But the real jackpot turned out that Captain Elmer was Joyce Kilmer’s commanding officer in the regiment’s Intelligence Section. Now I had an intimate look at the famous poet from the perspective of his commander. That was something no other historian had ever uncovered. You can imagine my elation.

- MH: Any other incidents like that?

SH Response: Well, one of the soldiers that really interested me was Sgt. Richard O’Neill, New York’s most decorated hero of the war. I’d read that he’d kept a war diary. I wanted it badly. But the O’Neill family just seemed to have vanished. O’Neill is quite a common name, as you know, and so I figured I’d have a heck of a time trying to locate the right family. I posted a query on one of the genealogy web pages, stating I was looking for the family of Richard O’Neill, who had won the Medal of Honor in the First World War, and hoped for the best. A year went by and I’d forgotten about my query. Then one day I received an e-mail from Ireland. The sender had written a book on the O’Neill clan and had received a letter from Michigan from a William Donovan O’Neill that he was sorry his family wasn’t in the book, that his father held the Medal of Honor. I looked up William Donovan O’Neill’s phone number and immediately called him. He was Richard’s son, all right, Col. Bill Donovan was his godfather and, astonishingly, he had the war diary!

14. MH: It sounds like half the fun of writing a book is in the research.

SH Response: No doubt. I feel like Sherlock Holmes tracking down families and gathering material that’s never been used in a book before, material that’s been overlooked by other historians.

15. MH: Have you always been a writer/historian?

SH Response: Always a writer who happens to love history. I started out in newspapers, following the tradition of my late grandfather who worked on the Kansas City Star (as did both my great uncles). He then became foreign editor of the old New York Herald. I stayed with newspapers for a few years but finally switched to corporate public relations. That’s where the money is. For a number of years I edited the General Electric magazine, Monogram. Because my wife had a great job, I was able to leave GE to pursue my dream as a freelancer. I wrote about Olympic history, working closely with the United States Olympic Committee as well as the International Society of Olympic Historians. But now, as you know, I can’t get enough of the Great War.

16. MH: Tell us what your next project is going to be Steve.

SH Response: I don’t want to tip my hand just yet. But I can tell you it’ll be another book on the Great War and this time it’ll be the tale of a regular army unit, an outfit that stopped the German advance on Paris. Then maybe I’ll get back to that book on the Olympic decathlon.

Thank you Steve, you have made a wonderful series of additions to the study of the First World War and of America’s contributions during the struggle.

To order Stephen L. Harris’s works at Amazon.com:

> Duty, Honor, Privilege: New York’s Silk Stocking Regiment and the Breaking of the Hindenburg Line (link)

> Harlem’s Hell Fighters: The African-American 369th Infantry in World War I (link)

> Duffy’s War: Fr. Francis Duffy, Wild Bill Donovan, and the Irish Fighting 69th in World War I (link)