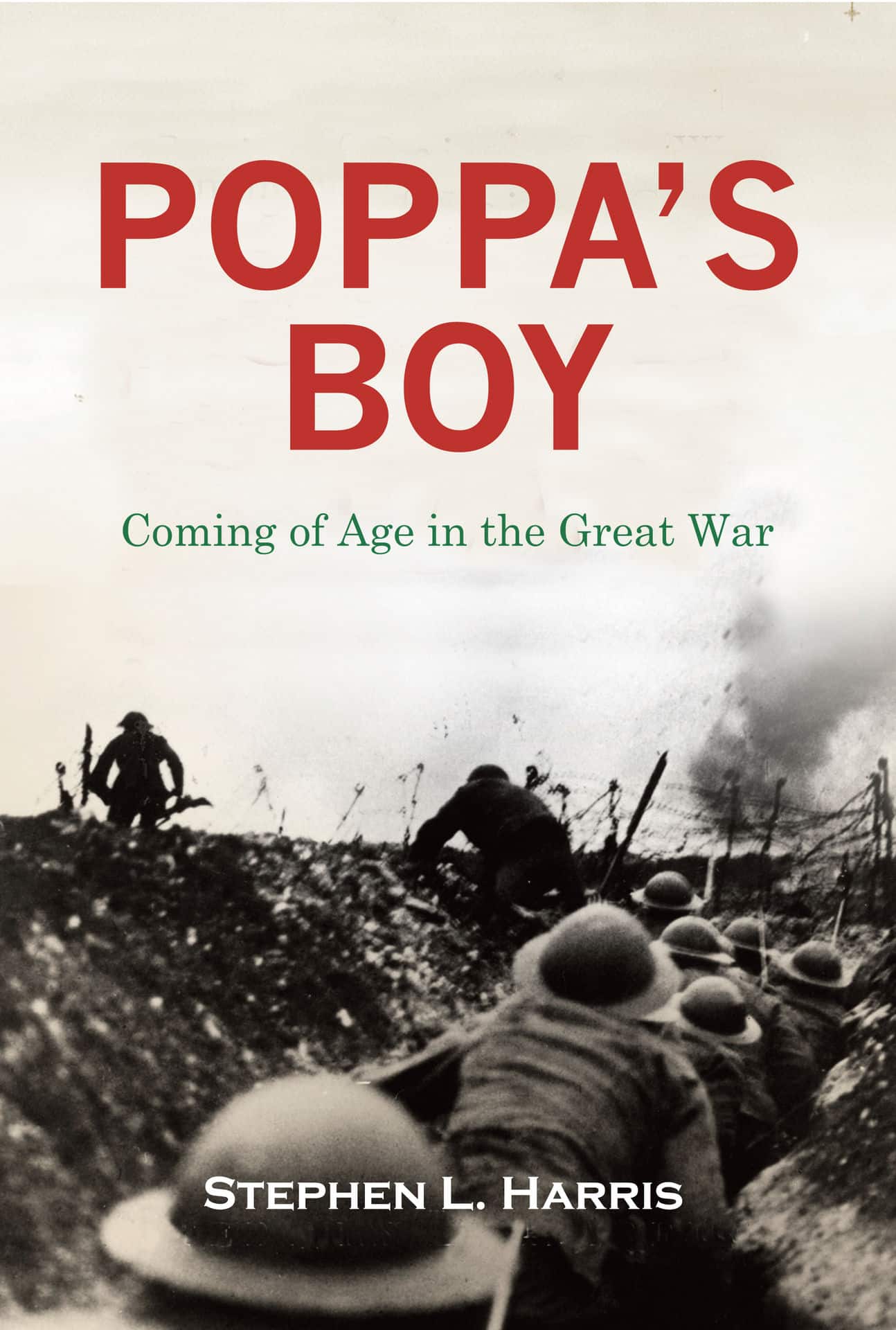

Poppa’s Boy: Coming of Age in the Great War

The year is 1917 and the United States has just declared war on Germany. Teenager Bucky

Riley, a Burlington, Vermont, native, is eager to join the American forces off to fight in what is

called the Great War now raging in Europe. The big reason—his father, a Rough Rider hero of

the Spanish-American War and famous war correspondent, believes Bucky is a “Momma’s

Boy,” rather than the rough and tumble “Poppa’s Boy” he wishes him to be. Bucky wants to

prove to his father and to himself that he’s not a Momma’s Boy. But he’s only 15—legally far too

young to join the Army—and that’s a problem. Nevertheless, Bucky thinks he knows a way

around the age issue. With his father off covering the war for a New York newspaper and not at

home and with his mother never going to let him go to war, Bucky runs away in the dark of night

to join the legendary Fighting 69th Regiment and make it to war-torn France to fight the Hun.

That’s when his adventures, romance and journey through hell begin—a journey that transforms

him from a “Momma’s Boy” to a “Poppa’s Boy.”

If you were going to teach a high school course on America’s part in World War One this book would make an excellent introductory text. It’s also a fascinating novel for adults since the story is so firmly rooted in New England and French place names, noted historical figures from Roosevelt to Father Duffy, and the organization, training and combat experience of relatively green America soldiers. All these are incorporated into the main story line: the adventures from 1917 to 1918 of a young lad nicknamed Bucky.

Bucky’s relationship with his father has never been an easy one. Luther “Rough” Riley had seen heroic action with Colonel Roosevelt in Cuba and out west with General Leonard Wood. He had hoped for a son who would follow in his footsteps, but instead got a Momma’s Boy. When America enters the Great War, Luther is one of the first to volunteer for Roosevelt’s planned battalion but when that falls through, he manages to get to France as a news reporter. Bucky’s own adventures begin after his father leaves home and when, at the age of fifteen, he decides to run away and enlist.

When he faces rejections because of his age, Bucky’s life takes on an almost Huckleberry Finn nature as he works his way down river on The Frank White, ‘a steam-driven, wooden towboat that’d seen better days.’ His intention is to get down to New York City and hopefully enlist there. Nothing is that easy, however. Complications arise in the form of an attractive young girl, Calliope Van Pelt, a victim of her parents’ divorce who is desperately trying to escape her father. Her brother, now a soldier, is also involved, as is an unforgiving Sheriff. More characters come into play before a dangerous flight on foot through a tough part of New York finally gets Bucky into the army—and eventually into the Fighting 69th Regiment.

The final third of Poppa’s Boy brings us to Bucky’s army training, his friendships and his fears (plus his love for Calliope). The author also interweaves into Bucky’s story the politics involved in the initial organization of an army that is to “go over there.” A salient feeling of the troops and officers alike is that they are going to take care of things in France, they are going to make the final difference, and that it “will all be over once we’re over there.” French sacrifices and efforts are somewhat acknowledged along the way, the British are ignored, and the Americans will save the day. But it will still be tough for Bucky.

How we got almost the entire Headquarters Company into that one freight car—fifty boys with rifles and packs and a few of them pretty much overweight—was a marvel. The moment we were all squashed in, with a lot of cussing and pushing and hunting for a place to squat, the heavy door rolled shut. At least it wasn’t locked. But we were in the dark until our eyes got used to it. Then we were off to Paris.

It’s hard to merge so much historical detail and actual people into a novel, but Stephen Harris has done it in such a way that fact combines easily with fiction. This, of course, is what a historical novel must do. The book’s resolution occurs, as it should, in its last pages when Bucky’s combat experience gives him enough to have nightmares for the rest of his life.

I waded into the Ourcq. Around me, bodies bobbed in the water that had turned pinkish from so much blood. More bodies littered the north bank and the hillside. And still more bodies had matted down much of the wheat. Mortar shells continued to hit the ground, exploding and gouging out holes and ripping off limbs of so many.

However, he is now no longer Momma’s Boy but in a very real way has become Poppa’s Boy. Stephen Harris has successfully turned his hand to the novel in this book after having written highly acclaimed histories of America’s role in World War One, and readers will appreciate and enjoy what he has achieved in this new endeavor

—Reviewed by David F. Beer, Tuesday, October 15, 2024

Bravo! The three-part structure and integration of impressive research combine to make the experiences of Bucky’s “coming of age” a compelling and totally engrossing tale. Particularly effective is the blending of geographic detail, historical data, a sense of contemporary social attitudes, and the horrors of WW I. I expected to enjoy your work, but I did not expect to be so emotionally moved.

—Thomas Brocco, former college dean

What a good story framed by the author’s knowledge of history. He winds the travels of a young boy who follows his father’s travel to WW1 in Europe and experiences the terror and heroics of that time. A best read for those young people searching for a purpose in life.

—Tom Hackett, financial executive